|

|

||

You Are Here: Issues > China Reports > Deconstructing Construction in China |

|||

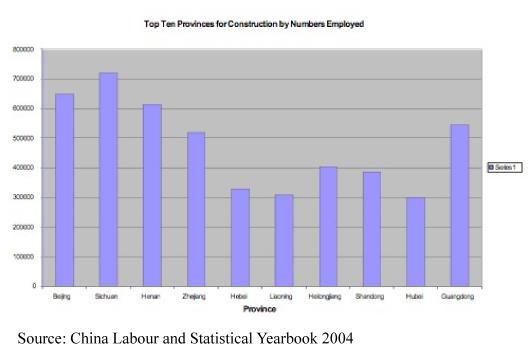

Unlike the manufacturing sector, foreign capital has not so far played a dominant role in the construction industry. Over 56 per cent of the 999 foreign construction companies registered in 2003 – just 1.5 per cent of the total number – were from Hong Kong and their larger presence is due to Hong Kong’s cultural and geographic proximities as well as the boost to economic cooperation that has accompanied the return to Chinese sovereignty since 1997. As of 2003, foreign investors came from 29 countries and the vast majority of them set up China-based construction enterprises between 1990 and 1995. Until recently, participation in construction projects by foreign companies was limited by a rule that restricted their access to projects backed – either by investment or through loans – by foreign governments. During the nineties Chinese government policy viewed the participation of foreign companies in the construction industry largely as a channel for technology transfer. Investment rules were changed to allow technology and know-how to be registered as capital investment. China’s first three years as a WTO member did not fully open up the construction market – classified by the WTO as trade in services – and the role of FDI remained strongest in the research and development field as opposed to construction itself. However, the lifting of restrictions on market access and national treatment are likely to change this scenario and the aforementioned factors driving the continued development of the domestic construction industry will also attract foreign companies. Perhaps the two most important changes that came into effect in late 2005 as a direct result of WTO commitments are: the lifting of the restriction that limited investment to projects backed by foreign governments; and permission for wholly owned foreign construction companies to set up shop. Consequently, even neighboring Asian construction companies, traditionally slow to invest outside their domestic markets, are showing increased interest in China. This is due not just due to improved opportunities in the China market but also to increased competition from foreign companies at home as capital moves with relative ease across borders. Japanese construction companies for example are piggy backing on investment in China from Japanese manufacturers by competing for factory construction. Almost inevitably, the next five years will see the increased activity by foreign companies in the construction industry as more foreign construction companies establish themselves and this process will be accompanied by mergers with, and acquisitions of, local construction enterprises. The Workforce Construction sites employ large numbers of workers on a day-hire basis. Even for skilled workers who are much more likely to be hired for the full term of a project, contracts are the exception rather than the norm. The dramatic rise of smaller highly specialized subcontractors providing workers to construction companies has made it very difficult to ascertain who is actually working for whom as has the presence of many construction workers on site without proper papers. This renders the reporting of any figures on the total number of workers employed in construction a hazardous affair. Unless stated otherwise, the statistics in this section are national labour statistics compiled by four government departments including the National Bureau of Statistics and are presented in an annual China Labour Statistical Yearbook (2004). While still far from foolproof, most observers recognise a gradual improvement and depoliticisation of statistics over the last decade. At the same time, it should also be remembered that there are default initiatives connected to tax and social security payments for under/over reporting by companies, local officials and provincial governments alike. The mid 80s saw the partial deregulation of employment practices. Managers and directors of employing units found themselves with much greater leeway in their hiring and firing practices. But even before this, the construction industry had been practicing fairly large scale sub contracting of cheap rural labour on specific projects. The practice had been the flash point for political polemics and struggles during the Cultural Revolution when ‘radicals’ condemned the practice as a sign of continuing capitalist relations in China. So it is not surprising that, more than any other industry, the construction industry witnessed the largest increase in employment between 1980 and 1985 when numbers employed jumped from 8.5 million to over 20 million. The increase has continued steadily ever since. In 2002 approximately 40 million workers were employed in construction, second only – if we exclude farming – to the wholesale, retail, trade and catering industries which are combined in Chinese industrial statistics. Approximately 80 per cent of these workers are not directly employed by urban enterprises. The chart below shows the top ten employers of construction workers in urban areas in 2003 by province/municipality. It is important to note that if we take 1994 as a starting point, the numbers involved in construction overall have increased from almost 32 million to almost 39 million in 2003, while the numbers working in urban areas have dropped from 11.1 million to eight million. This suggests that major infrastructure projects and the construction of small towns – part of the government’s urbanization programme – are accounting for the employment of large part of surplus labour from the countryside. . The 1997/98 crisis barely showed up in national statistics on employment in construction but it looked much more dramatic if we concentrate on the urban areas where numbers dropped from 10.3 million in 1997 to 8.8 million in 1998 as government policy adapted to the changed economic environment and reigned in urban construction projects. Numbers only started to rise again slowly in 2002. Increased mechanization and labour productivity in the cities will probably ensure a steady market-orientated fluctuation rather than dramatic increases in numbers employed on urban sites and projects. Urban construction sites have always employed large numbers of women. Over the last 10 years they have represented between 13-20 per cent of the total employees. In 2002 there were 1.4 million women workers employed in the construction industry. On site, women mostly do the unskilled heavy labouring jobs such as supplying bricks and blocks and cement mixes to bricklayers, site cleaning, loading and unloading of materials etc. The women are often kin or spouses of male workers on site. There are no figures available for women working on sites and projects in rural areas.

Almost all physical construction work is done by migrant workers. Conversely, very few migrant workers are involved in the management and administration of construction projects. However, as the contracting chain has become more specialized, some former construction workers are making use of their experience and contacts to set up businesses that supply labour and workers’ accommodation to construction companies. During research for this paper, we talked to the owner of a hostel in Shenzhen providing accommodation for construction workers mostly from Henan province, employed on a daily basis as interior painter and decorators. The hostel was run by a former road construction worker, Mr. Wang, also from Henan. There are thousands of such establishments operating on the fringe of legality in areas where migrant workers are concentrated and they are a vital if indirect link in the construction industry’s supply chain. While many construction workers live on site, the hostels provide recruiting grounds and contact points for both legal labour services companies and gang masters operating illegally.

|

|||