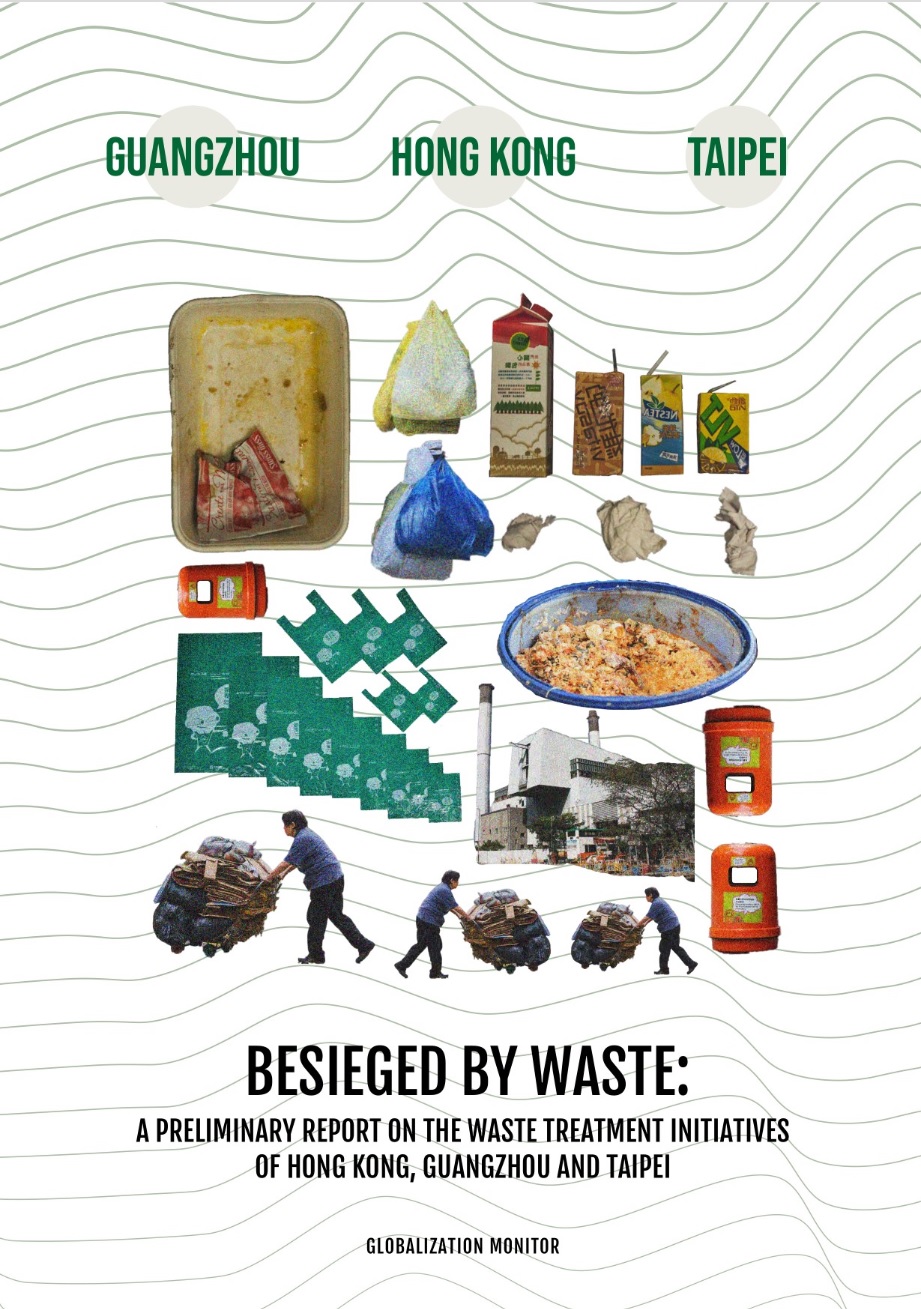

Hong Kong’s “cardboard siege” is indicative of how complex the waste treatment problem is. Waste pickers in Hong Kong often rely on collecting cardboard waste and selling them on to recyclers for a basic living. But when China decided it would stop importing 24 types of solid waste in 2017, used cardboard prices dropped drastically. As a result, many of waste pickers were pushed out of business and cardboard waste accumulated in the city’s streets. This experience demonstrates that paper recycling involves not only the public’s environmental awareness and corporations’ social conscience, but also a cross-border waste economy and even the Earth’s ecological balance, as we trace cardboard products through their supply chains back to the trees from which they came.

The piling up of garbage is a symptom of modern society’s sickness of consumerism. The monumental amounts of waste produced by a society predicated on buying new things and throwing away the old bring huge public health, economic and ecological threats. The predominant ways of treating waste—landfilling and incineration—are no better as they also cause different kinds of pollution and carbon emission. By encouraging overproduction and treating the waste that comes from these products almost as an afterthought, we are only irresponsibly accelerating humanity towards devastation.

Green movements in developed countries have been advocating for the reduction of waste at the source to save their cities from being besieged by waste. This report studies the waste treatment policies adopted by Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Taipei in the last 20 years specifically, with the goal of evaluating what made certain approaches work, raising society’s awareness and urging authorities to focus their energies on reducing waste at the source. This report studies also pays close attention to the working conditions of cleaners. While we advocate for the protection of nature and expect a hygienic living environment, it must not come at the expense of the rights of those whose work makes it possible. Without dignity for workers and just distribution, there can be no real justice in the environmental justice movement.

Hong Kong chapter analyses insisting on the principle of “positive non-interventionism” and refusing to act against the harmful externalities generated by the market have resulted in a waste management approach characterized by seeing waste as a problem emerging from the end of product lifecycles, in other words waste created during the manufacturing and marketing stages of commodity production is overlooked – despite the government has already set its target of reducing the city’s municipal waste disposal rate 20 years ago. In addition to criticizing Hong Kong’s waste strategy, which has long focused on landfilling or incinerating what society throws away, this chapter also portrays the employment situation of cleaners, revealing the phenomenon of cleaners facing increasing workload without being compensated appropriately.

The Guangzhou section of the report focuses on waste sorting in Guangzhou, analysing how it has been implemented and the issues affecting the participation of stakeholders—particularly sanitation workers—in order to make a comprehensive proposal about enhancing both environmental protection and workers’ rights.

Taipei chapter examines changes in policy and regulatory framework as well as the role of civil society with reference to the experience of bottom-up reforms in the history of Taiwan’s waste policy, which includes how civil society helped promote food waste as a legally-recognized recyclable and pushed for policy evaluation and changes through waste summit. In the second half of this chapter, the roles of and risks facing frontline cleaners under policy shifts are also discussed.